An Interview with Arthur Miller

I came across a Kennedy Center Honors Legend interview featuring Arthur Miller while combing through old Marilyn Monroe interviews. It was a two-and half-hour in-depth conversation between Miller and Mike Wallace that explored his life and career as a playwright and cultural icon. What I realized as I watched and listened was Arthur Miller's wise social commentary on past events and his insight into the human condition in relation to society that is still so relevant today.

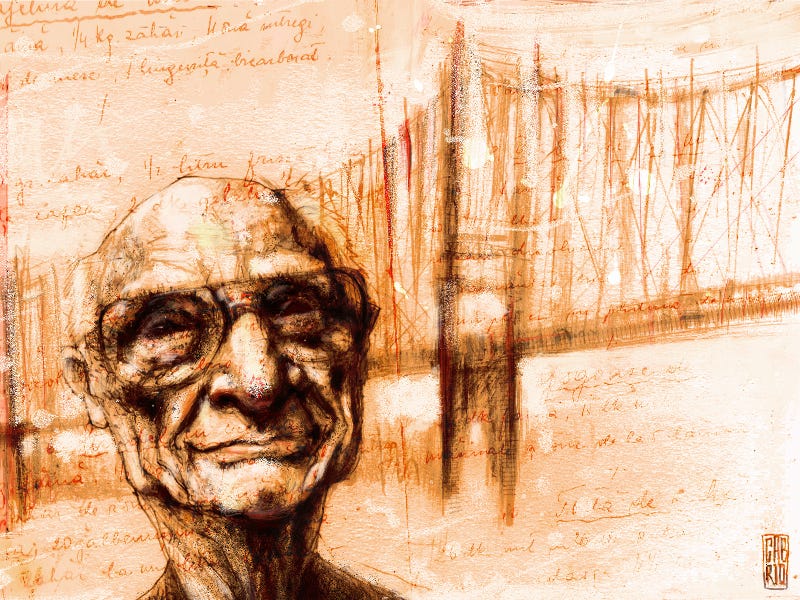

Arthur Miller was a tall, serious-looking man with deep laugh lines outlining his mouth that contradicted his dark, penetrating gaze. A candid figure in this interview, he lacked a filter and observed life through a pragmatic lens, some of which he claimed were the effects of coming of age in the Great Depression. Society, according to Arthur, was the sum of its parts and the division of class and status, an inevitable impulse of the human condition, could be tempered through a humble understanding of human connection.

Miller’s family had fallen from the heights of the 1920s upper-middle class of Manhattan and ended up living a poorer rural life in Brooklyn in the 1930s, as hard as it is now to believe Brooklyn was ever considered rural. He was a man who understood the privileges of financial wealth but also valued the humbleness and hard labor of working-class life. This gave Arthur insight into what influenced the relentless drive for success in American life and the plight of the everyday individual trying to make sense of the world. There was a certain level of passion and drive behind Arthur’s writing to depict society as it was from a real-world perspective.

Miller's first introduction to theatre was through his mother, who frequented Manhattan "road company" theatres (16:20). In this part of the interview, he briefly alludes to the daily life of Manhattan women in the 1920s. I imagine the social importance of matriarchal community building of the time taking place in these theatres. Arthur’s mother gave him the foundation on which to build a connection between American life and the theatre plays that reflected upon it. He was clever and navigated his early writing career with the passion and zeal of an artist, and with a mission to fulfill an innate desire for storytelling. It was a calling of sorts he could not ignore.

One of the first books Arthur took an interest in as a teenager was Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (Dostoevsky F. 1866). An interesting choice and a prelude to the moral premise of many plays he would write and to his personal life when faced with an accusation of communist associations by the U.S. government of the 1950s McCarthy era.

Arthur’s first play was No Villain (Miller A. 1936), a story about a workers' strike during the downfall of the financial market in the 1930s and the ideals of intellectualism that struggle to coexist with the realities of working-class life.

Arthur, a traditionalist at heart, makes no bones about the importance of family, community, and moral values that provide one with the stability to survive challenging times. In the interview, he briefly touches on the suicides that occurred following the financial crash of the 1930s while loosely quoting a 1930 New York Times article stating that statistically, 100,000 people would not be in the psychological condition to ever work again due to the shock of it all. He points out with an acute sense of awareness how delicate our societal structure is without checks and balances and how many American towns continued to experience economic hardship into the 1980s when this interview was done. (21:30)

Miller went on to discuss his subsequent successes and failures as a playwright, including mentioning his radio scripts for the Cavalcade of America (28:07), a corporate propaganda drama series funded by DuPont that involved constitutional story lines featuring George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and the topic of slavery as a means to clean their image after WWII. This foray into the early days of media propaganda and its use to fool the public by drawing sympathies is telling. Cavalcade of America was a pay-the-bills side gig for Arthur while he worked on more serious endeavors such as Death of a Salesman (Miller A. 1949).

Although I am far too young to have lived through it, McCarthyism is brought up several times during the interview. Mike Wallace inquires about Arthur Miller’s experience when he was suspected of communist activities in the early to mid-fifties. Arthur states, matter-of-factly, that he did attend a few writers’ meetings where Marxist ideals were discussed. He then went on to explain the details of his interrogation by government officials, in which he was " not allowed to confer with a lawyer” (1:10:40) while he was bombarded by questions. He provided some details of his subsequent court hearings, which included an attempt by prosecutors at create a passport misuse case to compensate for insufficient evidence. The case was eventually thrown out in an appeals court. Miller mentioned a few points that I thought were fair and still relevant today, such as if we are unable to express our political opinions and thoughts about societal ideals, we are conceding to thought control and another’s moral superiority, no matter what side of the aisle we sit on. (1:21:26) Fittingly, Miller goes on to discuss The Crucible (Miller A. 1953), his 1953 play about the Salem witch trials which played in Poland and was claimed a hit by communist officials. (1:39:00) Oh, the irony of it all!

Fast forward to the late 1950s and early 1960s, Miller discusses the decline of the American theatre and the potential causes, including skyrocketing ticket prices as a result of greed and a monopoly of New York Times theatre critics lambasting the American theatre in favor of the more sophisticated and high-brow British theatre, which causes a major New York landmark to close its doors. (2:01:26) There are a few inferences made in this part of the interview that I find particularly compelling such as, the power critics hold when they do not have competition from opposing critics, pointing out that contention tempers the monopoly of power. Arthur also explains the effects of rising ticket prices and the disappearance of a vital community of working-class intellectuals supporting the theatre (45:37). Greed kills the heart of a community. We can say this about the music concert venues of the 1990s into the 2000s when ticket prices began to rise. Without an invested and informed audience, the performance loses its quality and begins to wither until it dies.

What stood out for me amid Miller’s comments on the downfall of the American theatre and its stories about traditional American life from the perspective of regular working-class people, was the inference that when a pretentious intellectual class monopolizes the flow of information, they control the narrative at all costs due to an assumed authority, betting on the public’s ignorance for validation. Mike Wallace interjected by quoting critics that claimed the themes of family responsibility, “guilt and betrayal in the family, consequences of one's actions, dread of failure in a society” that were common themes in American theatre were "old fashioned" and could not be taken seriously unlike the “modern themes” of the British theatre that included “alienation, angst, and anomy.” (2:01:04) Sound familiar?

Miller goes on to say, referring to the more favorable modern plays, “These plays became more profound as social comment, but became narrower in terms of story, characterization, and the traditions of storytelling in the theatre.” (1:59:40)

Despite all the politics within the theatre community, there was a changing cultural shift in the mid-1950s to 1960s with the advent of television and changing societal proprieties that were moving away from the struggle of the common man of the 1930s Depression Era and the traditional American patriotism of the 1940s. Arthur goes on to convey the perceptions that Europeans had of Death of a Salesman in comparison to the American audience. The former seeing in the play the idea that a “small man can still dream” while their American counterparts viewed it as “the system grinding down this man.” Goes to show that, in Arthur's words, "we become too adapted to the reigning ideas of a society" and take them for granted or idealize what could be in its place. Miller claims an American high school went as far as to ban the production of Death of a Salesman in the school theatre because they viewed it as anti-American. (1:53:28)

Arthur points out that the Chinese adapted a version of Death of a Salesman quite accurately and asserted with giddiness and a grin that the Chinese share a similar humor as Americans. (1:52:13) I was surprised to hear this, but with further contemplation, I understood this as a mimicking of sorts or an admiration from afar that perhaps the Chinese adopted this humor. In the same breath, I also understood Miller’s comment that he thought the Chinese understood the American will, sense of irony, and Jewish American matriarchal family structure with which he could identify. (1:04:20) Arthur Miller admits that in the end, we are all one people with similar foundations regardless of culture.

I want to end this with one central theme I observed in the interview: The importance community life plays in the livelihood of our culture. Without contention, opposing perspectives, variety in intellect and creativity, and the freedom to think and speak from a place of truth and experience, meaning in life ceases to exist, and a society dies. We benefit from having physical spaces such as the theatre to congregate and debate, but we also must embrace and value podcasts, the resurrection of independent journalism, and the creation of various online platforms that give us a voice in the greater community.

Sources

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. The Russian Messenger, 1866.

Miller, Arthur. Death of a Salesman. Viking Press, 1949.

Miller, Arthur. No Villian. 1936.

Miller, Arthur. The Crucible. Viking Press, 1953.

The Kennedy Center. “Kennedy Center Honors Legend: Arthur Miller (In-Depth Interview)" YouTube, 4 Nov. 2022. Retrieved from

Wikipedia contributors. "Cavalcade of America." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 8 Jan. 2023. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cavalcade_of_America&oldid=1120395906